Harvard Health Blog

Read posts from experts at Harvard Health Publishing covering a variety of health topics and perspectives on medical news.

Welcome to this Decision Guide about PSA testing.

Prostate-specific antigen, or PSA, is a blood test used by many doctors to screen for prostate cancer. If you’ve had your PSA level checked, you may have been told that your results were “normal” or “abnormal.” However, some men would like to know more about what their PSA level means.

This imaging technique, which uses a powerful magnet and a computer to generate pictures of the body’s organs and tissues, can be used to diagnose prostate cancer or pinpoint the tumor’s location.

Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) can create images of the prostate gland using sound waves. Doctors may recommend TRUS when they suspect prostate cancer based on an abnormal DRE or an elevated PSA.

Researchers are developing more screening tests for prostate cancer. Like the PSA test, they rely on biomarkers, such as antigens or proteins, which are elevated or may only be present in men who have prostate cancer. The hope is that these newer tests will better detect existing cancers (better sensitivity), and will not raise the alarm for cancer when it is not present (better specificity).

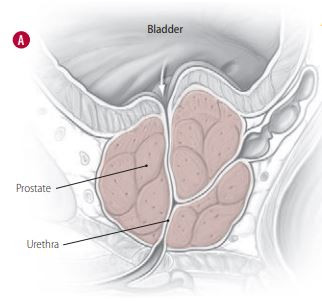

In this test, the doctor inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum and feels the surface of the prostate to determine whether it is swollen or has any lumps or abnormally textured areas (see Figure 1). This exam also helps doctors screen for diseases of the rectum, such as rectal cancer.

The National Cancer Institute discontinued the study after finding evidence that selenium and vitamin E supplements did not prevent prostate cancer.

The jury is still out on whether intermittent hormone therapy, which involves repeated cycles of hormone therapy followed by breaks in treatment, might help patients live longer than continuous hormone therapy. But Patrick Kirby’s story might help patients who are debating various options in hormone therapy.

Spotting blood in your semen can be worrisome, but it’s usually not cause for alarm.

Penile rehabilitation, which typically consists of oral or injected medications, alone or with other interventions, may help restore erectile function after treatment for prostate cancer. However, this therapy remains controversial.

Even if your doctor has given you a clean bill of health, beware: problems getting or keeping an erection firm enough for sexual intercourse may signal trouble, especially cardiovascular disease, down the road.

Three Harvard doctors talk about who needs to be treated for BPH, what medications should be prescribed, and what side effects you need to be aware of.

A look at treatment options and trade-offs

If you are like many of the 14 million men in the United States who have been diagnosed with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), you’ve probably been taking the same medication, at the same dose, for years. If so, consider the experiences of two patients, both of whom were taking some type of medication for BPH. Their names have been changed, but all other details are accurate (see “Jack Muriel” and “Henry Banks”).

Penile implants, an option patients with erectile dysfunction probably hear little about, might offer a lasting and satisfying “cure.” Abraham Morgentaler, M.D., director of Men’s Health Boston, explains how.

Regular physical activity can help keep you — and your prostate — healthy

By now, we’ve all heard about the value of exercise in maintaining good health. Literally hundreds of studies conducted over more than half a century demonstrate that regular exercise pares down your risk of developing some deadly problems, including heart disease, stroke, and certain types of cancer (colorectal cancer, for example). It also eases the toll of chronic ailments like high blood pressure, diabetes, and arthritis.

Two registered dietitians from Harvard-affiliated hospitals tout the benefits of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains

“What can I eat to reduce my risk of developing prostate cancer?” That’s one of the most common questions physicians hear from men concerned about prostate health. Undoubtedly, many hope to hear their doctor rattle off a few foods guaranteed to shield them from disease. Although some foods have been linked with reduced risk of prostate cancer, the proof is lacking, at least for now.

When it comes to prostate cancer and other prostate diseases, how accurate are the statistics we hear? Can patients rely on reported figures to determine their risk of suffering complications such as incontinence and impotence? Why do data vary from one organization to another? Three experts discuss these questions and the growing field of outcomes research.

Mr. Williams, a successful business owner in his mid-60s, describes how he was able to maintain his sex life and other aspects of his physical emotional well-being during and after treatment for prostate cancer.

How one man persisted for almost two years in an effort to remedy one of the most bothersome possible side effects of prostate cancer treatment, and what men facing therapeutic decisions can learn from his experience.

When cancer advances despite primary hormone therapy

We often hear the term prostate cancer and assume it is one disease. Practically speaking, it is. On a molecular level, however, scientists are revealing a far more complex picture. Cancer has an innate ability to adapt to its surroundings. As it progresses, cancer cells tend to change, morphing to a point where the differences between tumor cells can be dramatic. That’s why some researchers believe late-stage prostate cancer is more accurately described as a mix of cancer cell types.

An interview with renowned urology researcher E. David Crawford, M.D., about the state of clinical trials on prostate health

Can hormone therapy extend the lives of men with advanced prostate cancer? Might a drug traditionally prescribed to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) help prevent prostate cancer? Does a short course of hormone therapy prior to a radical prostatectomy prevent or delay cancer’s return?

Marc B. Garnick, M.D., provides an overview of possible treatments that need more study, including cryotherapy, HIFU, and focal therapies.

Marc B. Garnick, M.D., discusses what biochemical recurrence means and what your options are.